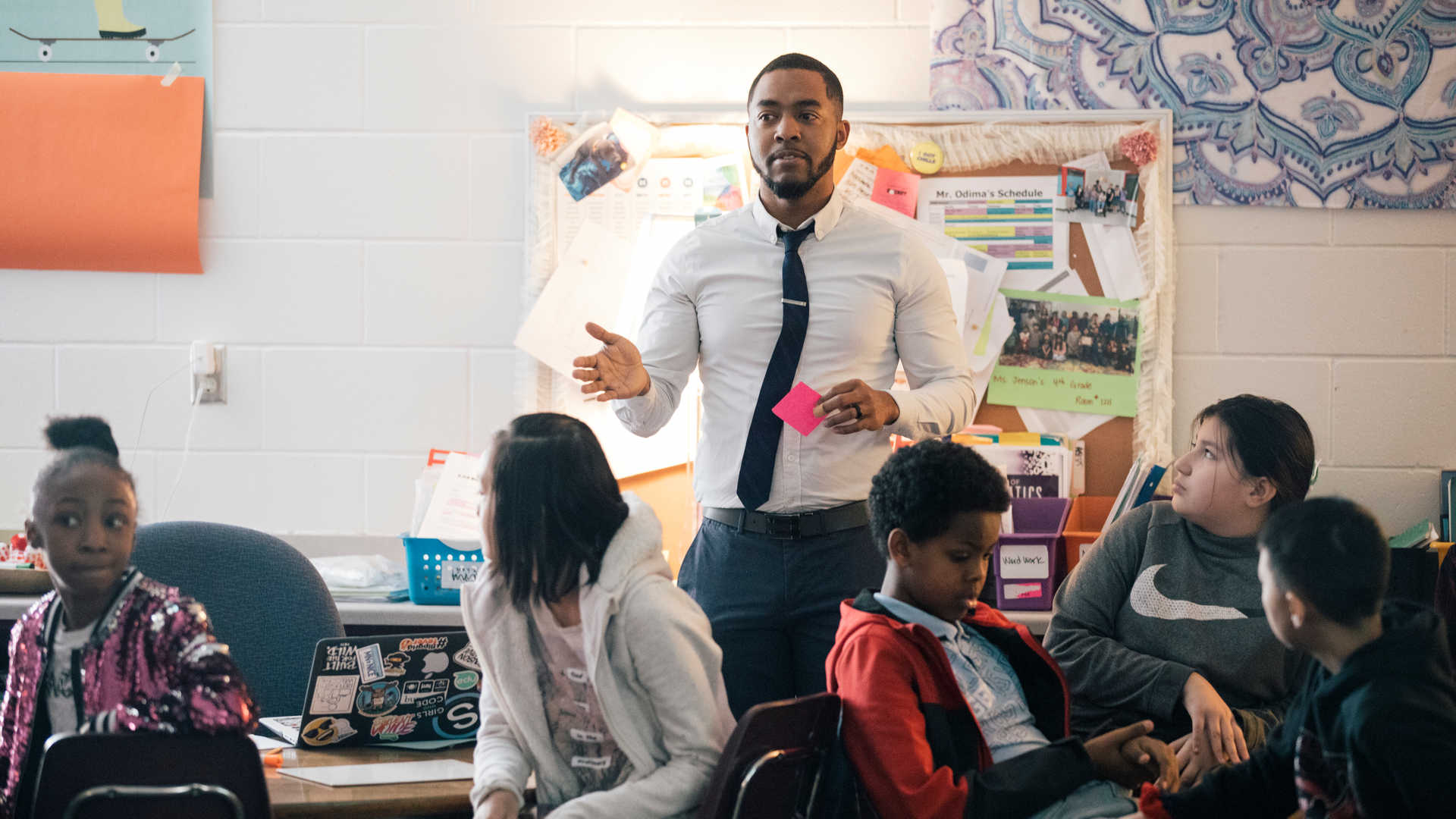

Authored by Martin Odima Jr. (St. Paul Public Schools) and L. Lynn Stansberry Brusnahan (University of St. Thomas)

The workload for all educators is intense. For special educators, it may be even greater due to the range of students’ instructional needs, the nuances of multiple classroom instructional formats, and the quantity of due process requirements (Stempien & Loeb, 2002). During the pandemic, educators have also dealt with both their own—and their students’—mental health and fatigue. Educators are told to engage in self-care; however, workloads leave little time to manage stress. On a particularly stressful day, Martin turned to Twitter to express his feelings about these responsibilities. His tweet, “Special education teachers do a lot. Like, a lot, a lot,” was viewed hundreds of thousands of times. This attention led the authors to dive into the “Like, a lot, a lot” for educators who encounter biases based on social identity and engage in roles to change current social justice structures in the educational system for students from their communities.

“Like, a Lot”: Social Identity

Due to a lack of diversity in the teacher workforce, not all students accrue the academic benefits of being taught by an educator from the same background (Villegas & Irvine, 2010). Martin, an African and Asian American male educator with a commitment to educational equity, inclusive practices, and social justice, wasn’t exposed to a Black educator until college. When Martin entered the field, he anticipated the typical challenges new educators experience, but he didn’t anticipate the amount of effort he would invest in navigation of racial structures. It is a lot! Martin works harder than others to prove his competence. Colleagues, consciously and unconsciously, treat teachers of color poorly and question their competency more often than their White counterparts (Bristol & Mentor, 2018). Black male teachers report that they are rarely recognized for their content knowledge, pedagogical abilities, and teaching skills (Jackson & Knight-Manuel, 2019). Conversations about race and its impact can be uncomfortable, but not having this dialogue because of “the discomfort of authentic racial engagement in a culture infused with racial disparity limits the ability to form authentic connections across racial lines, and results in a perpetual cycle that works to hold racism in place” (DiAngelo, 2011, p. 66). Martin has witnessed staff of color marginalized, disrespected, and dismissed while White teachers resist difficult conversations about how privilege manifests in educational settings. People of color who speak up and name bias in schools face hostility and are accused of being “too emotional,” “troublemakers,” or too “political” for pointing out conditions that harm individuals of color (Kohli, 2018). When there are racial incidents in schools or communities, these same teachers are often expected to take the lead in educating others while dealing with their own responses (Cornier et al., 2021).

“Like, a Lot, a Lot”: Social Justice Advocacy

Educators like Martin, who engage in social justice, invest a lot of time advocating for equity for students in special education programs who experience the intersectionality of having a disability and another social identity. Martin entered special education to be an agent of change, driven by an awareness of the needs of Black males in special education (Cornier, 2020). Students who disproportionately receive special education, physical segregation, and harsh applications of discipline policy need justice (Gorski, 2019). Martin has observed students in special education denied access to services because of this physical segregation. Martin invests time in justice work to provide access to the general education setting and interrupt systems that isolate students from curriculum, instruction, and peers without disabilities. Martin’s recognition of the inequities in students in special education not receiving access to all the general education curriculum led him to target science for instruction. He reached out to teachers and volunteers to brainstorm, collaborate, create, and implement a science program to engage students, regardless of their ability. The outcome was students in special education participated in the science fair for the first time. To support inclusion and ensure access, Martin has invested time co-teaching with a general education teacher to provide instruction to students with and without disabilities. Co-teaching requires extensive differentiation, innovation, and extra planning time. Additional responsibilities for teachers from underserved communities include being asked to be the disciplinarian for students experiencing behavioral challenges outside of their caseloads (Cornier et al., 2021).

Strategies

As a starting point, educators can participate in facilitated conversations and engage in critical introspection and reflective listening to understand bias, become aware of themselves and their personal bias, question understandings and beliefs, understand other perspectives, examine school contexts, and identify strategies (Safir, 2016; Staats, 2016). Conversations could include:

- What is bias (personal, institutional, and systemic)?

- Who am I (race, culture, ethnicity, socioeconomic group, language, sexual orientation, and gender)?

- How is my identity similar to and different from the identities of my students and other school personnel?

- What are my internal thoughts or beliefs about individuals based on identified differences?

- Where do I see biases playing out in schools? How does my school reproduce disparities in student outcomes or in the workload of colleagues?

- After listening to other perspectives, how are my thoughts or beliefs different?

- How can I disrupt my “autopilot” biased judgments about others based on my identity and understanding of the world?

- What fear or apprehension do I have about addressing these issues?

- How can I be an ally to individuals who experience racism in schools and adopt strategies that disrupt current inequities?

To advocate for social justice changes and gain access to curriculum for students with disabilities, educators can engage general education colleagues in conversations such as:

- What general education curriculum is not being provided to all students in special education?

- How can general and special education staff collaborate, share responsibility, and participate in different models of instruction to provide equitable access to the general education curriculum for students in special education?

Conclusion

Martin’s tweet received 14,903 engagements and 98 comments. The tweet resonated with educators and others around the country and ignited a banner for support, empathy, and compassion for special education teachers who do a lot. The national momentum focused on racial injustice makes this a prime time to call all educators to action to disrupt the disparity and acknowledge the “Like, a lot, a lot.” Educators can start by identifying bias and sharing in social justice work so as to not put this responsibility primarily on the shoulders of teachers who mirror students’ social identities.

References

Bristol, T. J., & Mentor, M. (2018). Policing and teaching: The positioning of Black male teachers as agents in the universal carceral apparatus. The Urban Review, 50(2), 218–234.

Cornier, C. (2020). They do it for the culture: Analyzing why Black men enter the field of special education. Multiple Voices: Disability, Race, and Language Intersections in Special Education, 20(2), 24–37.

Cornier, C. J., Wong, V., McGrew, J. J., Ruble, L. A., & Worrell, F. C. (2021). Stress, burnout, and mental health among teachers of color. Educators call for structural solutions. The Learning Professional, 42(1), 54–57.

DiAngelo, R. (2011). White fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54–70. Gorski, P. (2019). Avoiding racial equity detours. Educational Leadership, 76(7), 58–61.

Jackson, I., & Knight-Manuel, M. (2019). “Color does not equal consciousness”: Educators of color learning to enact a sociopolitical consciousness. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(1), 65–78.

Kohli, R. (2018). Behind school doors: The impact of hostile racial climates on urban teachers of color. Urban Education, 53(3), 307–333.

Safir, C. (2016). 5 keys to challenging implicit bias. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/keys-to-challengingimplicit-bias-shane-safir

Staats, C. (2016). Understanding implicit bias: What educators should know. American Educator, 39(4), 29.

Stempien, L. R. & Loeb, R. C. (2002). Differences in job satisfaction between general education and special education teachers: Implications for retention. Remedial and Special Education, 23(5), 258–267.

Villegas, A., & Irvine, J. (2010). Diversifying the teaching force: An examination of major arguments. The Urban Review, 42(3), 175– 192.